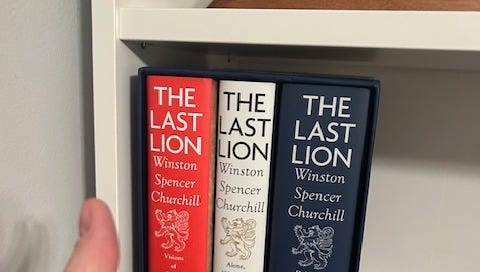

I’ve spent the last nine months plowing through William Manchester’s three-volume, 3,500 page masterpiece The Last Lion. The third and final volume was finished by Paul Reid when Manchester died before it could be completed, but he does a remarkable job of maintaining the voice and exhaustive clarity of Manchester’s style.

I’ll admit that the book has only served to strengthen my history addiction;1 Manchester (and later, Reid) deftly pulled on disparate strands of the historical record to assemble what amounts to a remarkably readable account of Churchill’s remarkable life. I’ll admit that I’m rather proud of finishing it.

I suppose that I am somewhat like the “old man” Churchill himself, who as a soldier serving in British India in his early twenties devoured Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, memorizing large portions of it and shifting his writing style to become more rich and concise.2 Except, I’m not a soldier, never left the county with the book (though I did read parts of it in Texas), memorized pretty much none of it, and learned all sorts of amazing new words that I’ve already forgotten except for a few saved in a note on my phone titled “Words to Use.”

I learned a lot, and would like to share some reflections with you, dear reader.

The Old Man

Churchill’s personality was nothing short of mystifying. One reason I know the authors were not fawning Churchillian sycophants is that I came away from the book realizing that I would probably dislike Churchill had I known him personally, and would certainly have hated working for him. At the close of WWII, Britain’s Chief of the Imperial General Staff (and avid diarist) Alain Brooke wrote in his diary that he felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude to God… for giving him the strength to work with Churchill for the last five or so years.

Indeed, Churchill cannot have been described as a kind man. He never really apologized to anyone, and was known to be impatient, prone to explode in a vituperative fury when a typist misheard a growled phrase or a butler brought the wrong cigar. Yet, by sheer force of indomitable will, Churchill led Britain (and the word) through some of the most momentous events of the 20th century.

Manchester helpfully pointed out that Churchill was fundamentally Victorian. He was born into an old English family of noble heritage (though a commoner himself) and was raised in that particularly peculiar world of the late 19th century British Empire. He fought in colonial wars, played polo, and was staunchly against woman suffrage until he realized that their votes might help him stay in politics.3

Politics was, as Reid claims, Churchill’s first and enduring love. After crafting himself into a public man through his war correspondence in India and South Africa Churchill stepped into the parliamentary ring, where he stayed for almost 55 years. It was where he was most comfortable - switching parties as political expediency required, and delivering speeches that listeners often took to be memorized but were actually delivered from carefully assembled speakers’ notes that in their arrangement looked more or less like a poem.

If politics was Churchill’s love, words were his art. He published more than six million words in his lifetime - more than Shakespeare and Dickens combined. Most interestingly, he knew full well what he was doing with his writing. Shortly after the close of WWII when the first write-ups of the conflict began to emerge (some casting Churchill in an unfavorable light), the “old man” decided he had to put his story to paper, which he did: in seven volumes that he described not as history, but his case. This kind of transparency is refreshing in an age where lots of writing seems to be masquerading as something it is not.

Great Man History

It has become fashionable in the last several decades to disparage what is sometimes referred to as “Great Man History,” which its detractors describe as a myopic focus on a few important or powerful men rather than the broad spectrum of individuals whose lives were intertwined with the events of history.

The result of this is “people’s history” or “social history,” attempting to tell the story of the past through the eyes of those who experienced it without the power to individually shape it on a macro level. The most famous example of this is Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, a very popular and very under-researched one-volume history of the US. Though social history has contributed enormously to our understanding of the past, we miss out if we neglect the study of people like Churchill who truly had a singular effect on world events.

One gets the impression from reading The Last Lion that Churchill was a distinctly unique demigod-like figure who found himself intertwined with history in a way reminiscent of Forrest Gump. Wondering if this was a result of the rose-tinted admiration of the authors, I queried a friend who read a different Churchill biography. His response: “you kind of get the impression that he, like, saved the world.”

I think that’s true. Though Churchill was wrong solidly half the time, he also had a level of foresight that exceeded his peers. Churchill’s biggest scandal was the Dardanelles affair, a naval gambit during WWI that attempted to take the Gallipoli peninsula and capture Constantinople, a likely do-able affair that was Tonya-Harding-ed by inept military leadership and delays. If it had been carried out as intended on paper, it is likely that it would have ended the war sooner, saved millions of lives, and saved the disaster of a peace initiated by the punitive Treaty of Versailles. Indeed, he developed a habit of referring to WWII as the “unnecessary war” for this reason.

About the Treaty of Versailles. When others thought it wise to cripple Germany after the Great War, Churchill saw the folly in this. Later, when the Appeasers in the British government looked on Hitler’s military buildup without concern while throttling British defense spending, Churchill was one of the lone voices in the wilderness warning of the impending doom. Churchill spent most of the 1930s in political exile, giving speech after speech to an empty House of Commons warning of the threat of the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe.

To say that Churchill was unsurprised when Germany broke through the Maginot line and pumped millions of Meth-fueled panzer divisions into Europe to dominate the continent would be an understatement. Discredited, the government fell apart and now Churchill was the only one standing who could take the office of Prime Minister as everything crumbled around him.

This was Churchill’s critical moment. Through 1939 and 1940 (and into 1941), Britain stood alone against an overwhelming Nazi Threat. The US was uninterested, France destroyed, the Commonwealths exhausted. Churchill faced daunting pressure to capitulate, but instead chose to stand alone against the looming red and black swastika spreading across the continent. It was at the peak of this moment, shortly after the defeat at Dunkirk and immediately preceding the Blitz, that Churchill delivered one of his most famous and Periclean speeches:

We shall not flag nor fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France and on the seas and oceans; we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air. We shall defend our island whatever the cost may be; we shall fight on beaches, landing grounds, in fields, in streets and on the hills. We shall never surrender and even if, which I do not for the moment believe, this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, will carry on the struggle until in God's good time the New World with all its power and might, sets forth to the liberation and rescue of the Old.

In this speech, he is telling Britons that this will be long, it will be hard, and it will be terrible, a prophecy that became reality only a few months later in September when the onslaught of the Blitz began.

Yet the people were willing to stand. What a remarkable example of leadership expressed through rhetoric and executed with will. During the nightly bombings of London during the Blitz, Churchill would watch the explosions and fires from the roof of the building atop his bunker, as aides and friends anxiously pleaded with him to come inside. The warrior in Churchill thrilled at the fight, while the statesman seethed at the loss. Somehow, this small island nation outlasted the Third Reich’s onslaught and held out long enough for Roosevelt (with some help from the Japanese) to bring the US around to involvement in the war.

Even still, Churchill’s June 1940 promise to take the fight to France went unfulfilled for four year, during which Britain faced loss after setback after defeat. Yet, when at the end of his life he was asked what year he would relive?

“Nineteen-Forty, every time.”

World-War Two

One of the pitfalls of “Great Man History” is that we only see the perspective of the Great Man at the top. We necessarily have a limited perspective of the experiences of those affected by the Great Man’s decisions. Churchill was an idea guy. He spent his days firing off memos to his staff suggestions any number of schemes, some of which were brilliant (the tank, floating harbors for amphibious invasions, the necessity of air power, etc) while many others were rather hair-brained. One American official said that if Churchill had 100 ideas a day, only 4 of them were any good. This may be uncharitable, but it speaks to the exhaustion that some felt with Churchill’s constant ideation.

The reality of leading in war-time means that your decisions lead to the deaths of others. In WWII, the scale of the death was unimaginable. I’ve included a chart below to demonstrate the scale of the slaughter, but one jarring aspect of the book was the rather causal way that massive causality numbers were tossed out - 2,000 here, 8,000 there, another 10,000 over ___ months, etc. When confronting sch figures it’s easy to forget that people die one at a time - and this is where history projects and shows like Band of Brothers, The Pacific, All The Light We Cannot See, and others can be helpful. They show us the raw brutality and savagery of the conflict that is outside of the scope of The Last Lion.

“Savage” barely begins to describe WWII. There’s the conflict itself, including the bombing of cities such as London, Prague, Dresden, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki. But the aspect that struck me the most was the Soviet Union. The USSR faced slaughter at an unimaginable scale - they single-handedly held back the Germans while the allies spent years preparing for an invasion of France and tooling around in North Africa.

But Stalin also murdered millions of his own citizens through famine and systematic executions. He followed Grant’s strategy of victory by attrition, but on a titanic scale. And when the Red Army swept through the states of Eastern Europe and into Germany, they brought with them rape, pillaging, and savage butchery (rolling over fleeing German refugees in tanks) at a level that is hard for me sitting in my peaceful and secure desk to comprehend.

We live in a violent and corruptible world, and it has fallen to people like Churchill to construct a cause and a reason to stand against its worst examples. Churchill had the task of navigating a testy alliance with “Uncle Joe,” as he called Stalin. Balancing the necessity of cooperation in war while trying to avoid a future one with the dominant communist power is a challenge of statesmanship that is admirable (though not mistake-free), and left me with an appreciation of the apocalyptic nature of WWII.

Conclusion

There’s much, much more I could say, but we’re already running a bit long, so I’ll wrap it up here. Churchill’s story has stuck in my head more than other biography I’ve read. Some of this is due to Manchester and Reid’s literary prowess. But how could you write a book about Churchill without paying homage to the Lion’s pen?

I’ll close with some of my favorite Churchill quotes from the book:

WSC to Violet Bonham-Carter, when they first met: “We are all worms, but I do believe I am a glow-worm.”

“When I get to to Heaven I mean to spend the a considerable portion of my five million years in painting, and so get to the bottom of the subject. But then I shall require a still gayer palette than I get here. There will be a whole range of wonderful new colours which will delight the celestial eye.”

When, in 1960, Churchill was told of Nye Bevan's death, he mumbled a few words of moderate respect, then paused for effect before asking, "Are you sure he's dead?"

“In the course of my life I have often had to eat my words, and I must confess that I have always found it a wholesome diet.”

“I am ready to meet my Maker. Whether my Maker is prepared for the great ordeal of meeting me is another matter.”

“A nation without a conscience is a nation without a soul. A nation without a soul is a nation that cannot live.”

"A sheep in sheep's clothing." (On Clement Atlee)

"We can always count on the Americans to do the right thing, after they have exhausted all the other possibilities."

"Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result."

Shane Gillis’ “early onset Republican” joke is apt

“Short words are best, and old words when short are the best of all”

And later founded the first college at Oxford (Churchill College) to admit men and women on an equal basis.

I enjoyed this post.

When we read Oppenheimer, I similarly, came away with a haunting sense that history was determined by the great men (people). It didn't have to be Churchill, it could be Busch, but it would have been and will continue to be "those" people. A sense mind you. A sense.

Also, yes. You are as great as Churchill.